Wartime coronavirus powers could hurt our democracy, without keeping us safe

Wartime

coronavirus powers could hurt our democracy, without keeping us safe

By: Cass

Mudde

Taken from:

The Guardian

We are not

at war with a virus. I don’t care how many politicians say it, from Xi

Jinping’s “people’s war” to Donald Trump’s “our big war”, or how many pundits

repeat it: we are not “at war” with the coronavirus. I know that in deeply

militarized countries like the US, the term “war” is now simply used to

emphasize the importance of an issue – from the non-existent “war on Christmas”

that conservatives talk about to the liberal “war on poverty”. But words have

meanings, and often real consequences, as we are still seeing in the “war on

drugs” and “war on terror”.

During a

war, the liberal democratic order is temporarily suspended, and extraordinary

measures are passed that significantly extend state powers and limit the

population’s rights. Some of the extended state powers only marginally infringe

upon the lives and rights of citizens, such as the creation of a “war economy”

(ie making economic production subservient to wartime efforts), but others have

traumatic consequences, such as the mass internment of Japanese Americans

during the second world war.

Across the

world, government leaders have declared (and extended) states of emergency, in

countries such as Spain, provinces such as Nova Scotia, Canada, and cities such

as Murfreesboro, Tennessee. I’m writing this column in my liberal college town

of Athens, Georgia, which declared a state of emergency a week ago and recently

added a “shelter-in-place” ordinance to it – which is partly undermined by the

much laxer response by nextdoor (Republican-run) Oconee county, so that Athens

residents can still dine and shop there.

State-of-emergency

measures are necessary in a real crisis, whether economic or health-related,

but they can be taken without the use of “war” language. They also should be

strictly related to the crisis at hand and proportional to the threat. At this

stage, the threat of contagion is very high, which means that measures to limit

the movement of people are legitimized.

Similarly,

most countries are woefully ill-prepared for the pandemic, with hospitals

dangerously overcrowded and underresourced, requiring urgent state

intervention. In addition to using massive funds to buy much-needed medical

supplies, this could also include enlisting the military to create temporary

hospitals, as New York is currently doing.

But many

politicians have gone much further, trying to use the health crisis to push

through dubious repressive legislation. For instance, in the United Kingdom,

where the Conservative government response so far has shown almost criminal

negligence, Boris Johnson has pushed through a draconian “coronavirus bill”,

which, among others, gives police and immigration officials sweeping powers to

arrest people suspected of carrying the coronavirus – this could make innocent

Brits of Chinese descent targets of state repression in a similar way that

post-9/11 measures have targeted innocent British Muslims.

In Israel,

the embattled prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, hoped that the coronavirus

could do what three elections have failed to achieve: extend his government

rule and keep him out of prison. Linking anti-corona measures to anti-terrorism

measures, Netanyahu proposed a package that critics have called

“anti-democratic” and has led to public protests in several Israeli cities.

Never to be

outdone, the Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, has jumped on the

coronavirus to push the final nail in the coffin of the country’s bruised and

battered democracy. On Monday, the Fidesz party-controlled government will vote

on a law that, according to one prominent critic, would “give Viktor Orbán

dictatorial powers under a state of emergency to fight the coronavirus”.

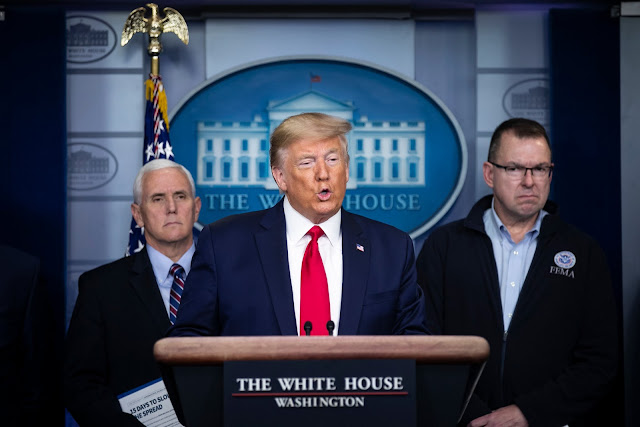

In the US,

President Donald Trump, forced to finally acknowledge the reality and

seriousness of the coronavirus pandemic after weeks of delusional statements,

is starting to see the political potential of the crisis. In a recent speech,

he stated, in his own unique English: “I view it as a, in a sense, a wartime

president.”

What this

“wartime presidency” could look like we could see in the emergency powers the

Department of Justice “quietly asked” Congress for. Most involve,

unsurprisingly, powers to further restrict immigration – undoubtedly influenced

by the anti-immigration zealot Stephen Miller, Trump’s longest-serving key

adviser (outside of members of his own family). It also includes the request to

grant chief judges the power to detain people indefinitely without trial, which

critics fear could mean the suspension of habeas corpus (the constitutional

right to appear before a judge after arrest and seek release).

There are

very serious problems with many of the proposed measures, many of them similar

to the repressive measures taken after 9/11. First, in many cases the proposals

are combinations of repressive measures that are unrelated to this specific

crisis. Second, many measures are disproportional to the threat we face –

habeas corpus is at the heart of the rule of law; should we really sacrifice

that for a health crisis whose lethality is still largely unknown? Third, while

they are all explicitly billed as “emergency measures”, limited to that

emergency, the language is often vague and could be used to justify (endless)

extensions. We know from experience that temporary measures often become

permanent measures.

To prevent

another Patriot Act, each new “emergency measure” should be assessed individually

on the basis of three clear questions: what is its contribution to the

fight against the coronavirus?; what are its negative consequences for

liberal democracy?; when will it be abolished? If any of these three

questions cannot be adequately answered, the measure should be rejected.

While it is

important to take the threat of the coronavirus seriously – really, people,

stay at home! – and to provide the state with the powers it needs to fight the

pandemic, we should not let our fear be used to drag us into yet another false

“war”. Because if we do, politicians will use it once again to strengthen the

already far too strong repressive powers of our surveillance states.

Comments

Post a Comment