We need a post-liberal order now

We need a

post-liberal order now

By: Yuval

Noah Harari

Taken from:

The Economist

For several

generations, the world has been governed by what today we call “the global

liberal order”. Behind these lofty words is the idea that all humans share some

core experiences, values and interests, and that no human group is inherently

superior to all others. Cooperation is therefore more sensible than conflict.

All humans should work together to protect their common values and advance

their common interests. And the best way to foster such cooperation is to ease

the movement of ideas, goods, money and people across the globe.

Though the

global liberal order has many faults and problems, it has proved superior to

all alternatives. The liberal world of the early 21st century is more

prosperous, healthy and peaceful than ever before. For the first time in human

history, starvation kills fewer people than obesity; plagues kill fewer people

than old age; and violence kills fewer people than accidents. When I was six months

old I didn’t die in an epidemic, thanks to medicines discovered by foreign

scientists in distant lands. When I was three I didn’t starve to death, thanks

to wheat grown by foreign farmers thousands of kilometers away. And when I was

eleven I wasn’t obliterated in a nuclear war, thanks to agreements signed by

foreign leaders on the other side of the planet. If you think we should go back

to some pre-liberal golden age, please name the year in which humankind was in

better shape than in the early 21st century. Was it 1918? 1718? 1218?

Nevertheless,

people all over the world are now losing faith in the liberal order.

Nationalist and religious views that privilege one human group over all others

are back in vogue. Governments are increasingly restricting the flow of ideas,

goods, money and people. Walls are popping up everywhere, both on the ground

and in cyberspace. Immigration is out, tariffs are in.

If the

liberal order is collapsing, what new kind of global order might replace it? So

far, those who challenge the liberal order do so mainly on a national level.

They have many ideas about how to advance the interests of their particular

country, but they don’t have a viable vision for how the world as a whole

should function. For example, Russian nationalism can be a reasonable guide for

running the affairs of Russia, but Russian nationalism has no plan for the rest

of humanity. Unless, of course, nationalism morphs into imperialism, and calls

for one nation to conquer and rule the entire world. A century ago, several

nationalist movements indeed harboured such imperialist fantasies. Today’s

nationalists, whether in Russia, Turkey, Italy or China, so far refrain from

advocating global conquest.

In place of

violently establishing a global empire, some nationalists such as Steve Bannon,

Viktor Orban, the Northern League in Italy and the British Brexiteers dream

about a peaceful “Nationalist International”. They argue that all nations today

face the same enemies. The bogeymen of globalism, multiculturalism and immigration

are threatening to destroy the traditions and identities of all nations.

Therefore nationalists across the world should make common cause in opposing

these global forces.

Hungarians, Italians, Turks and Israelis should build

walls, erect fences and slow down the movement of people, goods, money and

ideas.

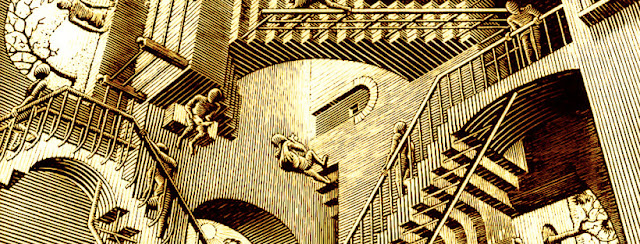

The world

will then be divided into distinct nation-states, each with its own sacred

identity and traditions. Based on mutual respect for these differing

identities, all nation-states could cooperate and trade peacefully with one

another. Hungary will be Hungarian, Turkey will be Turkish, Israel will be

Israeli, and everyone will know who they are and what is their proper place in

the world. It will be a world without immigration, without universal values,

without multiculturalism, and without a global elite—but with peaceful

international relations and some trade. In a word, the “Nationalist

International” envisions the world as a network of walled-but-friendly

fortresses.

Many people

would think this is quite a reasonable vision. Why isn’t it a viable

alternative to the liberal order? Two things should be noted about it. First,

it is still a comparatively liberal vision. It assumes that no human group is

superior to all others, that no nation should dominate its peers, and that

international cooperation is better than conflict. In fact, liberalism and

nationalism were originally closely aligned with one another. The 19th century

liberal nationalists, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini in Italy,

and Adam Mickiewicz in Poland, dreamt about precisely such an international

liberal order of peacefully-coexisting nations.

The second

thing to note about this vision of friendly fortresses is that it has been

tried—and it failed spectacularly. All attempts to divide the world into

clear-cut nations have so far resulted in war and genocide. When the heirs of

Garibaldi, Mazzini and Mickiewicz managed to overthrow the multi-ethnic

Habsburg Empire, it proved impossible to find a clear line dividing Italians

from Slovenes or Poles from Ukrainians.

This had

set the stage for the second world war. The key problem with the network of

fortresses is that each national fortress wants a bit more land, security and

prosperity for itself at the expense of the neighbors, and without the help of

universal values and global organisations, rival fortresses cannot agree on any

common rules. Walled fortresses are seldom friendly.

But if you

happen to live inside a particularly strong fortress, such as America or Russia,

why should you care? Some nationalists indeed adopt a more extreme isolationist

position. They don’t believe in either a global empire or in a global network

of fortresses. Instead, they deny the necessity of any global order whatsoever.

“Our fortress should just raise the drawbridges,” they say, “and the rest of

the world can go to hell. We should refuse entry to foreign people, foreign

ideas and foreign goods, and as long as our walls are stout and the guards are

loyal, who cares what happens to the foreigners?”

Such

extreme isolationism, however, is completely divorced from economic realities.

Without a global trade network, all existing national economies will

collapse—including that of North Korea. Many countries will not be able even to

feed themselves without imports, and prices of almost all products will

skyrocket. The made-in-China shirt I am wearing cost me about $5. If it had

been produced by Israeli workers from Israeli-grown cotton using Israeli-made

machines powered by non-existing Israeli oil, it may well have cost ten times

as much. Nationalist leaders from Donald Trump to Vladimir Putin may therefore

heap abuse on the global trade network, but none thinks seriously of taking

their country completely out of that network. And we cannot have a global trade

network without some global order that sets the rules of the game.

Even more

importantly, whether people like it or not, humankind today faces three common

problems that make a mockery of all national borders, and that can only be

solved through global cooperation.

These are nuclear war, climate change and

technological disruption. You cannot build a wall against nuclear winter or

against global warming, and no nation can regulate artificial intelligence (AI)

or bioengineering single-handedly. It won’t be enough if only the European

Union forbids producing killer robots or only America bans

genetically-engineering human babies. Due to the immense potential of such

disruptive technologies, if even one country decides to pursue these high-risk

high-gain paths, other countries will be forced to follow its dangerous lead

for fear of being left behind.

An AI arms

race or a biotechnological arms race almost guarantees the worst outcome.

Whoever wins the arms race, the loser will likely be humanity itself. For in an

arms race, all regulations will collapse. Consider, for example, conducting

genetic-engineering experiments on human babies.

Every country will say: “We

don’t want to conduct such experiments—we are the good guys. But how do we know

our rivals are not doing it? We cannot afford to remain behind. So we must do

it before them.”

Similarly,

consider developing autonomous-weapon systems, that can decide for themselves

whether to shoot and kill people. Again, every country will say: “This is a

very dangerous technology, and it should be regulated carefully. But we don’t

trust our rivals to regulate it, so we must develop it first”.

The only

thing that can prevent such destructive arms races is greater trust between

countries. This is not an impossible mission. If today the Germans promise the

French: “Trust us, we aren’t developing killer robots in a secret laboratory

under the Bavarian Alps,” the French are likely to believe the Germans, despite

the terrible history of these two countries. We need to build such trust

globally. We need to reach a point when Americans and Chinese can trust one

another like the French and Germans.

Similarly,

we need to create a global safety-net to protect humans against the economic

shocks that AI is likely to cause. Automation will create immense new wealth in

high-tech hubs such as Silicon Valley, while the worst effects will be felt in

developing countries whose economies depend on cheap manual labor. There will

be more jobs to software engineers in California, but fewer jobs to Mexican

factory workers and truck drivers. We now have a global economy, but politics

is still very national.

Unless we find solutions on a global level to the

disruptions caused by AI, entire countries might collapse, and the resulting

chaos, violence and waves of immigration will destabilise the entire world.

This is the

proper perspective to look at recent developments such as Brexit. In itself,

Brexit isn’t necessarily a bad idea. But is this what Britain and the EU should

be dealing with right now? How does Brexit help prevent nuclear war? How does

Brexit help prevent climate change? How does Brexit help regulate artificial

intelligence and bioengineering? Instead of helping, Brexit makes it harder to

solve all of these problems. Every minute that Britain and the EU spend on

Brexit is one less minute they spend on preventing climate change and on

regulating AI.

In order to

survive and flourish in the 21st century, humankind needs effective global

cooperation, and so far the only viable blueprint for such cooperation is

offered by liberalism. Nevertheless, governments all over the world are

undermining the foundations of the liberal order, and the world is turning into

a network of fortresses. The first to feel the impact are the weakest members

of humanity, who find themselves without any fortress willing to protect them:

refugees, illegal migrants, persecuted minorities. But if the walls keep

rising, eventually the whole of humankind will feel the squeeze.

Yet that is

not our inescapable destiny. We can still push forward with a truly global

agenda, going beyond mere trade agreements, and stressing the loyalty all

humans should owe to our species and our planet. Identities are forged through

crisis. Humankind now faces the triple crisis of nuclear war, climate change

and technological disruption. Unless humans realise their common predicament

and make common cause, they are unlikely to survive this crisis. Just as in the

previous century total industrial war forged “a nation” out of many disparate

groups, so in the 21st century the existential global crisis might forge a

human collective out of disparate nations.

Creating a

mass global identity need not prove to be an impossible mission. After all,

feeling loyal to humankind and to planet Earth is not inherently more difficult

than feeling loyal to a nation comprising millions of strangers I have never

met and numerous provinces I have never visited.

Contrary to common wisdom,

there is nothing natural about nationalism. It is not rooted in human biology

or psychology. True, humans are social animals through and through, with group

loyalty imprinted in our genes. However, for millions of years Homo sapiens and

its hominid ancestors lived in small intimate communities numbering no more

than a few dozen people. Humans therefore easily develop loyalty to small

groups such as families, tribes and villages, in which everyone knows everyone

else. But it is hardly natural for humans to be loyal to millions of utter

strangers.

Such mass

loyalties have appeared only in the last few thousand years—yesterday morning,

on the timetable of evolution—and they coalesced in order to deal with large

scale problems that small tribes could not solve by themselves. In the 21st

century we face global problems that even large nations cannot solve by

themselves, hence it makes sense to switch at least some of our loyalties to a

global identity. Humans naturally feel loyal to 100 relatives and friends they

know intimately. It was extremely hard to make humans feel loyal to 100 million

strangers they have never met. But nationalism managed to do exactly that. Now

all we need to do is make humans feel loyal to 8 billion strangers they have

never met. This is a far less daunting task.

It is true

that in order to forge collective identities, humans almost always need some

threatening common enemy. But we now have three such enemies: nuclear war,

climate change and technological disruption. If you can get Americans to close

ranks behind you by shouting “the Mexicans will take your jobs!” perhaps you

could get Americans and Mexicans to make common cause by shouting “the robots

will take your jobs!”.

That does

not mean that humans will completely give up their unique cultural, religious

or national identities. I can be loyal at one and the same time to several

identities—to my family, my village, my profession, my country, and also to my

planet and the whole human species.

It is true

that sometimes different loyalties might collide, and then it is not easy to

decide what to do. But who said life was easy? Life is difficult. Deal with it.

Sometimes we put work before family, sometimes family before work. Similarly,

sometimes we need to put the national interest first, but there are occasions

when we need to privilege the global interests of humankind.

What does

all that mean in practice? Well, when the next elections come along, and

politicians are asking you to vote for them, ask these politicians four

questions:

* If you

are elected, what actions will you take to lessen the risks of nuclear war?

* What

actions will you take to lessen the risks of climate change?

* What

actions will you take to regulate disruptive technologies such as AI and

bioengineering?

* And

finally, how do you see the world of 2040? What is your worst-case scenario,

and what is your vision for the best-case scenario?

If some

politicians don’t understand these questions, or if they constantly talk about

the past without being able to formulate a meaningful vision for the future,

don’t vote for such politicians.

Comments

Post a Comment